Brief History

“For much of the twentieth century, Asians were at greater risk of death by genocide or mass atrocities than people’s anywhere else in the world.”

-Professor Alexander Bellamy, University of Queensland

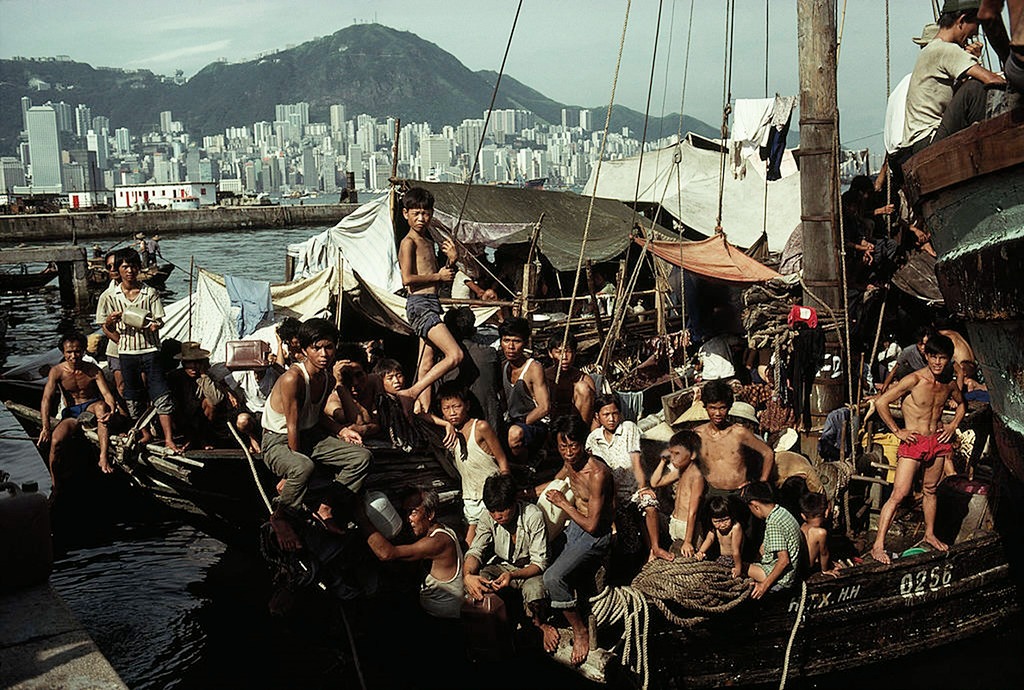

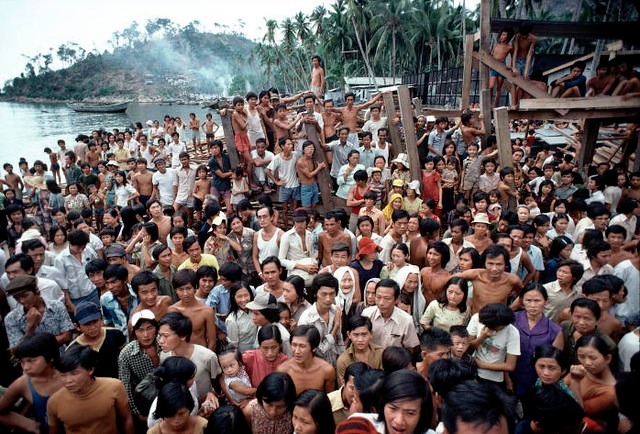

During the 20th century, Pacific Asia, encompassing both East and Southeast Asia, became a vast region swallowed by gruesome war and genocide. The involved conflicts, among others, include the American War in Vietnam, the Nanjing Massacre, and the Cambodian Genocide—all historically significant owing to their severely violent nature. For instance, the Nanjing Massacre, known colloquially as “The Rape of Nanjing”, cast a somber shadow over China after the murder and sexual abuse of hundreds of thousands of villagers from 1937 to 1938. For a period spanning over 20 years, Vietnam witnessed its nation crumple under the wrath of war, as civilians were subjected to torture, mutilation, and murder. In nearby Cambodia during the late 1970’s at the hands of the notoriously brutal communist party the Khmer Rouge, the country erupted into chaos due to mass killings with nearly a quarter of the Cambodian population decimated. In the broader Pacific Asian region, countries such as the Philippines, Korea, and Indonesia additionally grappled with violence, conflict, and oppression during periods of political upheaval. As a whole, East Asia emerged from the other end of the century with millions of casualties, leaving behind a legacy of pain, trauma, and severe psychological scars.

Mental Health Affects

“I’m always scared. Because of what I saw before, because of what I went through. I’m always scared that it will happen again in the future.”

-Kim Le, Vietnamese refugee

Given the severity of the 20th-century conflicts in Pacific Asia, it is well established that asylum seekers and refugees experience high rates of depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorders. The American Psychiatric Association estimates that the rate of significant trauma-born mental health struggles in this population is as high as one in three individuals. However, only a small portion of Pacific Asians are receiving mental health services. Why are Asians less likely to seek help?

Asia’s deep-rooted culture of emotional suppression and restraint is a major barrier to the progress of mental health within these communities. This principle can be traced back to cultural values of maintaining social reputation. Asian society attaches deep value to outward impressions; revealing personal weaknesses or challenges is considered humiliating or “losing face”. Furthermore, the stability of Asian society is firmly structured around family and community caregiving. Prioritizing one’s personal struggles over the interests of the larger society is often perceived as selfish or arrogant, and can unravel a larger societal structure. As reiterated by psychiatrist Dr. Geoffrey Liu, “Mental illness is seen…as taking away a person’s ability to care for others. For that reason, it’s seen as taking away someone’s identity or purpose. It’s the ultimate form of shame.” Lastly, linguistic barriers are a very fundamental challenge to mental health supports. With over 35 percent of Asians possessing limited English proficiency, there is clearly an insufficient number of mental health providers who can communicate in native languages to provide needed support. The lack of psychological professionals proficient in the language, as well as the stigmas surrounding mental health that challenge inherent Asian cultural values, results in a perpetual cycle of untreated struggle.

A Solution

“The truth about culture is that the only way you can change it is by changing the way individuals work with one another. If you can change that, then you will find the culture has changed.”

-Professor Roger Martin, University of Toronto

To support Pacific Asian immigrants and refugees, there is a clear demand for more mental health resources. Specifically, it is critical that these organizations, therapists, and support groups are fluent in the cultural needs of this unique population. One such organization, The Center for Empowering Refugees and Immigrants (CERI) in Oakland, California, focuses on providing mental health services to immigrants and refugees affected by war and trauma. CERI puts a strong emphasis on the “trusted messenger model,” a deliberate method where the provider offering services is from the same community as the individual in need. This sensitive strategy not only removes language and cultural barriers, it allows safe discussion around sensitive topics such as losing face and acceptance of prioritizing individual needs. By utilizing individuals who are part of the community they serve, mental health services can be delivered in a manner that respects cultural nuances and forms trusted relationships. By forming such a community, the discussion of disparities in the mental health community is opened; a dialogue is started. It is through this support, acceptance, and openness that a new society is formed. The weight of this community can shift cultural norms and pave the way towards fostering a culture of acceptance for a vulnerable population that has been long overlooked.

By Frances Carlson