This article aims to investigate whether the political crisis experienced by Venezuela between 2016 and 2019 is related to the migratory flow of nationals from that country to Brazil since the beginning of President Nicolás Maduro’s government in 2013. The hypothesis of the study is that the worsening of internal political tensions, combined with the economic downturn, would have led to an increase in the movement of Venezuelans towards Brazil. I will analyze the historical series of Venezuelan migration to Brazil and relate it to recent political and economic events in that country. Additionally, I will examine the measures taken by the Brazilian government to receive Venezuelan nationals, evaluating the context in which they were made.

Historical Context of Venezuela:

One cannot discuss Venezuelan politics in this century without mentioning the figure of Hugo Chávez, the charismatic leader who governed the country from 1999, when he was elected for his first term, until 2013, when he died while in office. A colonel in the army, Chávez attempted a coup d’état in 1992 but was defeated and imprisoned. Nevertheless, his popularity grew, and he began to emerge as a popular leader. After forming his own movement, dubbed “Bolivarianism,” Chávez won the elections, putting an end to an oligarchic pact that kept the three main parties in power through a limited democratic alternation.

Once elected, Chávez took advantage of high international oil prices to implement his policies of income redistribution and poverty eradication, which earned him high popularity in what was one of the most unequal countries in Latin America. Supported by his high popular approval, Chávez began to reform all the country’s power structures, increasingly expanding his own powers. A new constitution was promulgated in 1999, expanding executive power. Moreover, Chavismo began occupying positions in the National Assembly and the Judiciary, and the government became increasingly authoritarian, leading to growing opposition to his government, especially among the middle and upper classes. Venezuela also began to face external pressures, notably from the United States, which denounced what they perceived as the dictatorial nature of the Chavista regime. At the time of his death, Chávez was a strong charismatic leader who had controlled virtually all spheres of power, including through political persecution.

Before his death in 2013, weakened by cancer in his final months, Chávez appointed Nicolás Maduro, then serving as Vice President and a trusted confidant of the deceased leader. Maduro held elections that same year, emerging victorious in a vote marked by accusations of fraud and political persecution. Upon assuming power, Maduro sought to rely on Chávez’s legacy, but the internal and external circumstances were no longer the same. Oil prices had fallen, and the Venezuelan economy was suffering from low growth and dynamism, partly due to unilateral sanctions imposed by the United States. The socioeconomic crisis and cuts in social programs caused Maduro’s popularity to decline, leading to increased opposition to his government. At the same time, in an attempt to control the situation, Maduro’s government became increasingly authoritarian, systematically accusing the opposition, allegedly supported by the United States, of trying to sabotage the country.

The 2016/2017 Crisis:

May 2016, as widely reported by the international press, was marked by intense protests against Maduro’s government. The anti-Maduro camp announced at the time that it had collected 1.8 million signatures in just five days in favor of holding a referendum to revoke President Maduro’s mandate. It is important to note that the number of signatures supposedly obtained was nine times the amount required by law to call a referendum. Additionally, in the first months of 2016, nearly 4,000 protests against the government were reported, primarily demanding access to food. During this period, supermarket looting and shortages of essential items were recorded. In September 2016, between 950,000 and 1.1 million people protested in Caracas in what was considered one of the largest demonstrations in the country’s recent history.

The following year, Venezuela, according to international organizations cited by the international press, was considered the second most violent country in the world due to looting and urban conflicts. The sense of insecurity even led several countries to recommend their citizens leave Venezuela. The economic crisis also worsened. According to data from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), in 2017, the country’s annual inflation reached 1,642%, and unemployment rose to 27%. The inflationary spiral quickly escalated, reaching 10,000,000% by the end of 2019. These figures differ from those released by the Central Bank of Venezuela (BCV), which reported 10,000%, but these are considered unreliable by international organizations. The country’s GDP, according to IMF data, experienced continuous declines between 2017 and 2019, and the Bolívar, the national currency, suffered significant devaluation, prompting a rush for dollars and a kind of “informal dollarization.” These difficulties, with no real prospect of improvement, seem to have driven an increasing number of Venezuelans to seek opportunities in other countries, migrating in large numbers.

The following year, Venezuela, according to international organizations cited by the international press, was considered the second most violent country in the world due to looting and urban conflicts. The sense of insecurity even led several countries to recommend their citizens leave Venezuela. The economic crisis also worsened. According to data from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), in 2017, the country’s annual inflation reached 1,642%, and unemployment rose to 27%. The inflationary spiral quickly escalated, reaching 10,000,000% by the end of 2019. These figures differ from those released by the Central Bank of Venezuela (BCV), which reported 10,000%, but these are considered unreliable by international organizations. The country’s GDP, according to IMF data, experienced continuous declines between 2017 and 2019, and the Bolívar, the national currency, suffered significant devaluation, prompting a rush for dollars and a kind of “informal dollarization.” These difficulties, with no real prospect of improvement, seem to have driven an increasing number of Venezuelans to seek opportunities in other countries, migrating in large numbers.

Venezuelan Migration Processes:

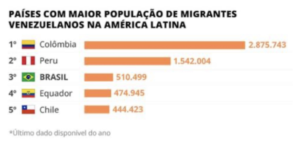

Between 2017 and 2018, almost 7% of the population was exiled (2.3 million people), according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). This is one of the most significant population movements in Latin America. The majority of Venezuelan migrants head to countries in the region, particularly those bordering Venezuela. The main destination is Colombia, followed by Peru. As would be expected, Venezuelan migrants first opt for countries with the same language, which allows for easier integration. Thus, Brazil, where Portuguese is the official language, would not be a priority destination. On the other hand, the extensive border between the two countries and Brazil’s stronger economic performance are attractive factors that cannot be overlooked.

The intensity of the migratory flow has forced some countries to take more radical measures regarding the entry of Venezuelan immigrants. Before the measures taken in 2018, an identity card was the only document required by Peru, Colombia, and Ecuador for migrants to enter these countries. However, starting in 2018, a passport was required, thus restricting the possibility of legal entry into these countries. Nevertheless, irregular migration remains high, although precise numbers are not available.

Migration to Brazil:

Since the intensification of the crisis in 2017, more than 800,000 Venezuelans have entered Brazil, primarily through its northern border, seeking medical care, food, and new opportunities. Of these, about half decided to stay in the country. It is worth noting that, unlike Colombia, Peru, and Ecuador, Brazil continues to require only an identity card for entry into the country. Thus, Brazil has become one of the destinations with the highest demand for asylum.

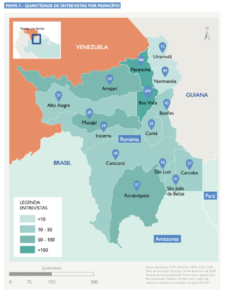

Most migrants enter the country through Brazil’s northern border, in the state of Roraima, and concentrate in the municipalities of Pacaraima and Boa Vista, the state capital. As a humanitarian response to the Venezuelan influx, the Brazilian Federal Government launched Operation Welcome in 2018. This operation involves the voluntary, safe, orderly, and free relocation of vulnerable Venezuelan refugees and migrants from Roraima to other cities in Brazil. Operation Welcome has relocated over 125,000 Venezuelan migrants and refugees across Brazil. In Boa Vista, between 2016 and June 2024, it is estimated that 9% of all public health services were provided to Venezuelan patients. To accommodate part of this population, 11 official shelters were established in Boa Vista and two in Pacaraima. They are managed by the Armed Forces and UNHCR. It is estimated that nearly 32,000 Venezuelans currently live in Boa Vista, representing about 8% of the total population.

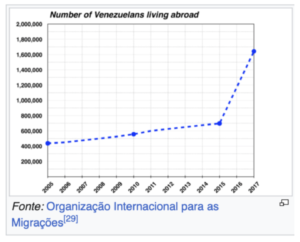

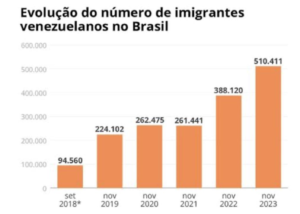

In this chart from a report by the International Organization for Migration (IOM), we can observe a growing increase in the number of Venezuelans in Brazil. In November 2023, there were approximately 510,000 Venezuelan immigrants in Brazil, almost six times more than in 2018.

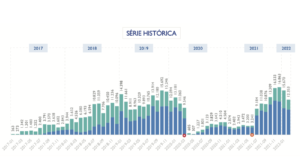

In this chart, taken from the Operation Welcome data, we can observe a constant increase in the demand for asylum in Brazil starting in 2017. In 2018, the increase in Venezuelan migrants heading to Brazil could be linked to the socio economic crisis in Venezuela and the aforementioned measures taken by the neighboring countries governed by Nicolás Maduro.

In this chart, taken from the Operation Welcome data, we can observe a constant increase in the demand for asylum in Brazil starting in 2017. In 2018, the increase in Venezuelan migrants heading to Brazil could be linked to the socio economic crisis in Venezuela and the aforementioned measures taken by the neighboring countries governed by Nicolás Maduro.

Analysis of the Internal Brazilian Context:

Beyond the external factors mentioned above that apparently contributed to the increased migratory flow of Venezuelans to Brazil, it is also important to consider Brazil’s internal context. Launched during Michel Temer’s administration in 2018, Operation Welcome reflected the government’s concern with the high number of Venezuelans arriving in the country through the northern border. The objective, as we have seen, was to provide humanitarian assistance and allow Venezuelan citizens to settle in the country in an orderly and safe manner. In its first year alone, it received a significantly higher number of migrants than in the years preceding the neighboring country’s crisis.

In 2019, there was a clear increase in the migratory flow towards Brazil, which may be a result of the worsening internal crisis in Venezuela, which in 2018 saw a new chapter with the highly contested re-election of Nicolás Maduro. At the same time, this increase may also be linked to the greater prominence that Operation Welcome gained during Jair Bolsonaro’s government, which began on January 1, 2019. During his electoral campaign, Jair Bolsonaro presented himself as an “anti-system” candidate who would end the left’s dominance in Brazil (the center-left Workers’ Party had won the last four presidential elections in the country) and realign the country with right-wing values, both domestically and internationally. Bolsonaro positioned himself as an anti-communist crusader, waging a cultural war against left-wing values.

Fulfilling his campaign promises, in January 2019, early in his government, Bolsonaro broke diplomatic relations with Caracas and announced a complete alignment of his foreign policy with that of the United States, then under the administration of Donald Trump, seen as a key ally on the international stage. It should be noted that the United States, regardless of the party in power, had long been trying to undermine the Venezuelan regime since Chávez’s presidency. By breaking diplomatic relations with Venezuela, Bolsonaro made an unprecedented move in the history of Brazilian foreign policy, signaling to the U.S. his commitment to the anti-Maduro agenda while also appealing to his electoral base. It is worth mentioning that Bolsonaro’s first Foreign Minister, Ernesto Araújo, was one of the staunchest advocates of the cultural war narrative.

In light of the above, there was an amplification of Operation Welcome in 2019, emphasizing the narrative that Bolsonaro is the president who will save Venezuelans, Brazil, and South America from the threats of the left. Indeed, Operation Welcome gained prominence and became increasingly publicized in Brazil by the then-president as part of his anti-communist crusade. In May 2019, the government released R$224 million for the assistance of Venezuelans in Brazil, demonstrating Bolsonaro’s desire to establish himself as a great defender of freedom and as a symbolic figure in the fight against socialism and communism.

These actions by Bolsonaro’s government may have impacted the increase in the number of Venezuelans entering Brazil in 2019, which, as observed, was even higher than in 2018. Although it is not possible to establish a direct correlation with the available data, it is possible that, in the short term, the Brazilian government’s active stance on receiving Venezuelans, as part of its political affirmation strategy, may have encouraged the increase in the number of migrants. However, by 2020 there was a sharp decline in the number of migrants, which could be explained by both internal Venezuelan issues and a possible cooling of the operation itself, which already seemed to have fulfilled its political purpose.

By Letícia Torres Valle da Fonseca