Pouya, 20 years old, Is an Iranian Student at Lille Business School who immigrated to France at the age of fifteen.

Can you recount some fond memories from your childhood? What type of schooling did you receive, and which traditions greatly influenced your identity?

“In Iran, the influence of propaganda begins as early as kindergarten. During a recent debate with a friend, we delved into the reality that, from the tender age of ten, individuals are expected to have a deep understanding of politics and religion in the country. In Iran, when you come from a family that is not religious you have to wear a mask every day. While at home you can freely debate about politics, outside the walls of your house you are not supposed to say anything against the regime. This became evident to me at the age of eight during ongoing elections when, emboldened by a school discussion, I shared my perspective. Following the class, the school director contacted my mother, urging her to refrain from discussing politics in my presence. Fortunately, I attended a private school, which afforded me a bit more leniency in this regard.��

Based on your earlier insights, could you elaborate on the functioning of the Iranian regime and share your sentiments toward it?

“In 1978, a profound revolution unfolded in Iran, reshaping the nation into an Islamic republic and establishing a theocratic regime rooted in Islamic principles. I strongly recommend the movie “Persepolis” if you want to gain deeper insights into Iran’s evolution over time.

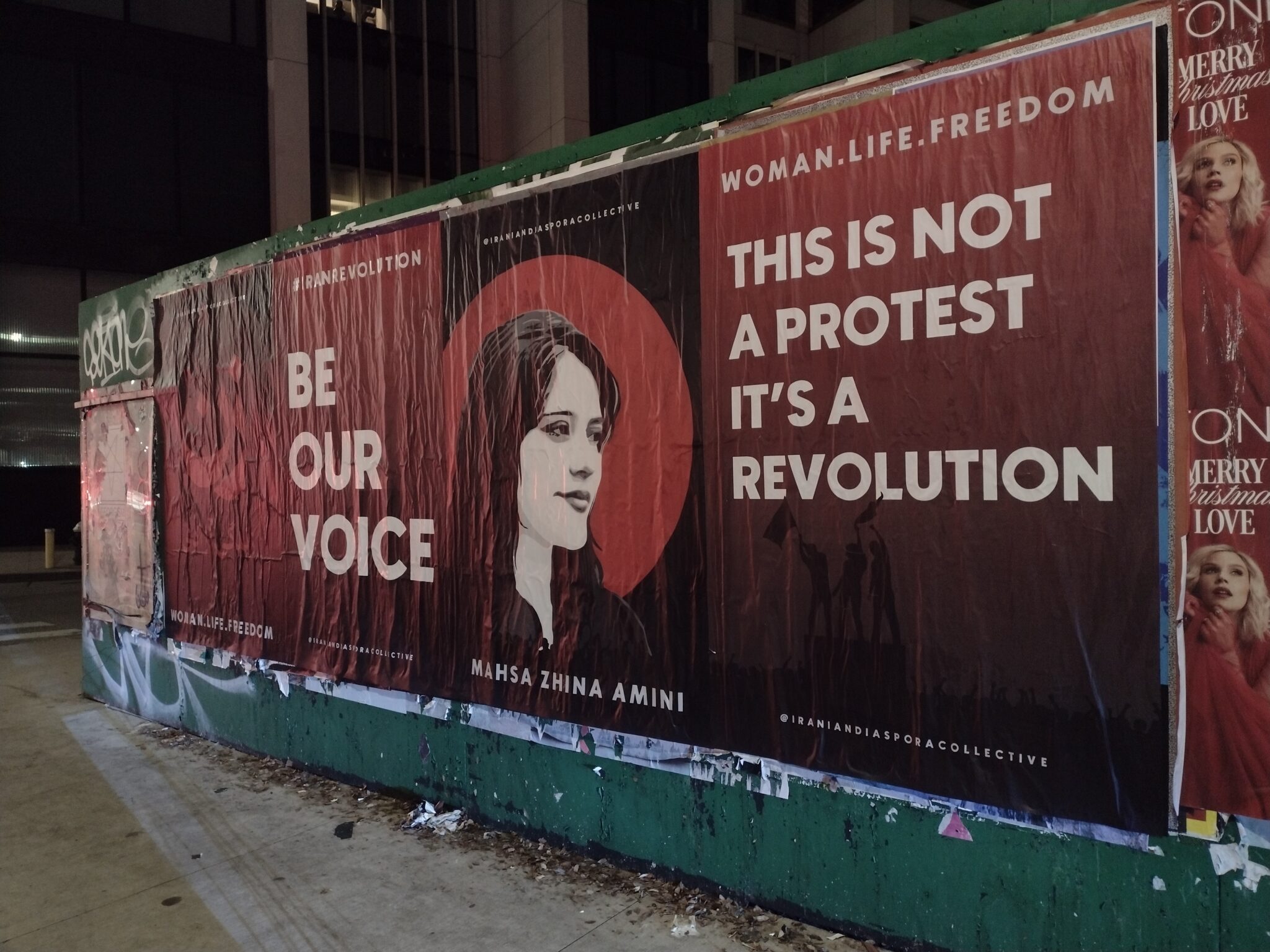

In my opinion, the death of Mahsa Amini and the subsequent emergence of the Women Life Freedom movement brought global attention to the inherent violence within the Iranian regime. This highlighted a crucial distinction: the Iranian citizens do not necessarily embody the regime’s values, contrary to common misconceptions. Personally, I feel frustrated towards the Iranian regime. However, a glimmer of hope emerges as the population increasingly protests against the regime. Although I have not been to Iran since the inception of this movement, I’ve learned from friends that the capital has witnessed a surge in freedom, which makes me optimistic.”

While the challenging conditions for women in Iran are often highlighted, what are the aspects that make you feel disadvantaged as a young man?

“The greatest disadvantage for me is knowing that I can’t go back to my country because if I do so I would be obliged to enroll in the military service. In Iran, there are two types of military service: the Artesh, representing the Iranian Army primarily stationed near the country’s borders, and the Sepah Pasdaran (سپاه پاسداران), a multi-service branch of the Iranian Armed Forces blacklisted by countries such as the USA. Because of their relationships and the fact that they supply weapons to organizations such as Hamas and Hezbollah, serving the Sepah Pasdaran would be like serving a terrorist group for me. This choice would not only limit my ability to leave Iran but also make obtaining a visa to move abroad impossible.

Furthermore, Iran strictly prohibits the consumption of alcohol, with 70 whiplashes and imprisonment for those caught. A friend of mine experienced this firsthand when he was caught drinking during his 18th birthday party, leading to lasting trauma and the need for psychological support. The frequent occurrence of such events in my homeland makes it challenging to find joy in life’s simple moments. Recognizing this reality reinforced my belief that moving to France was the best decision of my life.”

How do you feel about the media’s portrayal of Iranian people, and do you think there are misconceptions that you would like to address?

“I believe that prior to the Women Life Freedom movement, the Western media often depicted the Iranian population as mere reflections of the regime. One notable example that comes to mind is a movie narrating the story of a woman that has been kidnapped from her Iranian husband and obliged to stay in Iran for the rest of her life. This portrayal exemplifies how, before Mahsa Amini’s tragic death, Iranians were often characterized as closed-minded individuals solely dedicated to the Islamic religion.

Fortunately, with the advent of recent protests, the global community has come to realize that men are actively advocating for women’s rights in Iran. Sadly, many of my friends lost their lives in the past year while defending women’s rights. It was during this period, marked by an overwhelming number of deaths, that the international media began to present a more nuanced and accurate depiction of the Iranian people.”

Reflecting on your extensive time in Europe since arriving in France at a young age, what was the most difficult aspect of leaving your home country?

“Realizing that I was just fifteen and I was leaving my homeland forever made my arrival in France incredibly challenging. However, the most difficult aspect was to understand that the freedom I experience in France represents an unattainable dream in Iran. For all my journey I have struggled to accept that not all of my friends had my same opportunity “to escape” the country. During moments of joy with my friends here, I often find myself questioning, ‘Why can’t my people in Iran have the same?’

Just under two months ago, two men were arrested simply for dancing in a public space. This infuriates me, especially when contrasting it with countries like France or Italy, where people enjoy complete freedom to have fun and enjoy life.”

Throughout this journey, what have been the most prevalent emotions you’ve experienced?

“Frequent waves of anger have characterized this journey. This sentiment persists as I wait for my visa and resident permit. My entire life hangs on a precarious thread, and it seems that those responsible for these matters fail to comprehend the difficulty of the situation.

Last summer, while my international peers were eagerly making plans to traverse the globe after graduation, my primary concern revolved around the arrival of my resident permit and the assurance that I wouldn’t be compelled to return to my home country. I must confess that in moments like these, feelings of anger and envy towards my friends often overwhelm me.”

What notable differences have you observed between the circumstances of young people in Iran and Europe, particularly in their beliefs, perspectives, traditions, and lifestyles?

“As mentioned earlier, in Iran, expressing opinions divergent from the official stance requires wearing a metaphorical mask. This underscores a fundamental distinction between Europeans and Iranians—wherein Europe embraces individuality, allowing people to be themselves and be accepted for who they truly are.

Furthermore, I hold the belief that the government, with its array of restrictions, has not only fueled resentment towards the regime but has also contributed to a broader discontent with the Islamic religion. Those Iranians fortunate enough to ‘escape’ often come to deeply appreciate the freedom they find abroad. Nevertheless, I believe that now almost everybody knows the truth that lies behind the Iranian regime. A compelling example is my mother’s experience; born after the revolution during a tumultuous war with Iraq, she was exposed to potent propaganda. Prior to my birth, she was devoutly religious and genuinely believed in the fairness of the regime. However, with the passing of Saddam Hussein, Iran gaining more influence, and the easing of propaganda with technological advancements, her perspective gradually shifted. Pursuing a Ph.D., she delved into the authentic values of Islam, revealing the radicalization of the Iranian republic. Today, the perspective of the Iranian population has undergone a profound transformation compared to two decades ago. The availability of VPNs has furthered this shift, providing people with awareness of life beyond Iran.”

In your opinion, what potential solutions could help to improve the situation in Iran?

“I believe that the Western world ought to exert increased pressure on the Iranian government. Simultaneously, it’s crucial to acknowledge that the policies adopted toward Iran can disproportionately affect the regime with a lesser impact on the population. By imposing sanctions or controlling the inflow of funds into Iran, there’s a risk of devaluing the currency, potentially causing significant hardships for the population. This impact could be particularly devastating for parents supporting their children abroad.

Furthermore, I advocate for a more nuanced understanding and approach to the current situation in Iran and for an implementation of scholarships specifically for Iranian individuals. This would foster educational opportunities and positively contribute to the empowerment of the Iranian community.”

What are your aspirations or hopes for the future of your country and for all of the young Iranian people who didn’t have your same chances?

“Each time I witness people joyfully dancing, celebrating, and relishing life’s pleasures, I find myself pondering why my family, friends and the people of my country can’t partake in the same simple joys. My heartfelt desire is for them to experience the precious gift of freedom. I am confident that once they attain this freedom, they will not only savor life’s moments more deeply but also come to appreciate the true richness of their existence.”

Carla Bartoli